Jessica Meloy’s daily routine isn’t anything out of the ordinary. She wakes up at 6:30 every day, eats breakfast and is soon on her way to school. Jessica melts into the crowds of people in our hallways. She goes unnoticed for the most part, save for her close friends.

She walks through the halls, periodically putting on smiles to make her friends stop worrying. It’s a normal day for Jessica, just as it is for most students at McLean. What’s not normal, however, is that Jessica is struggling to save her own life.

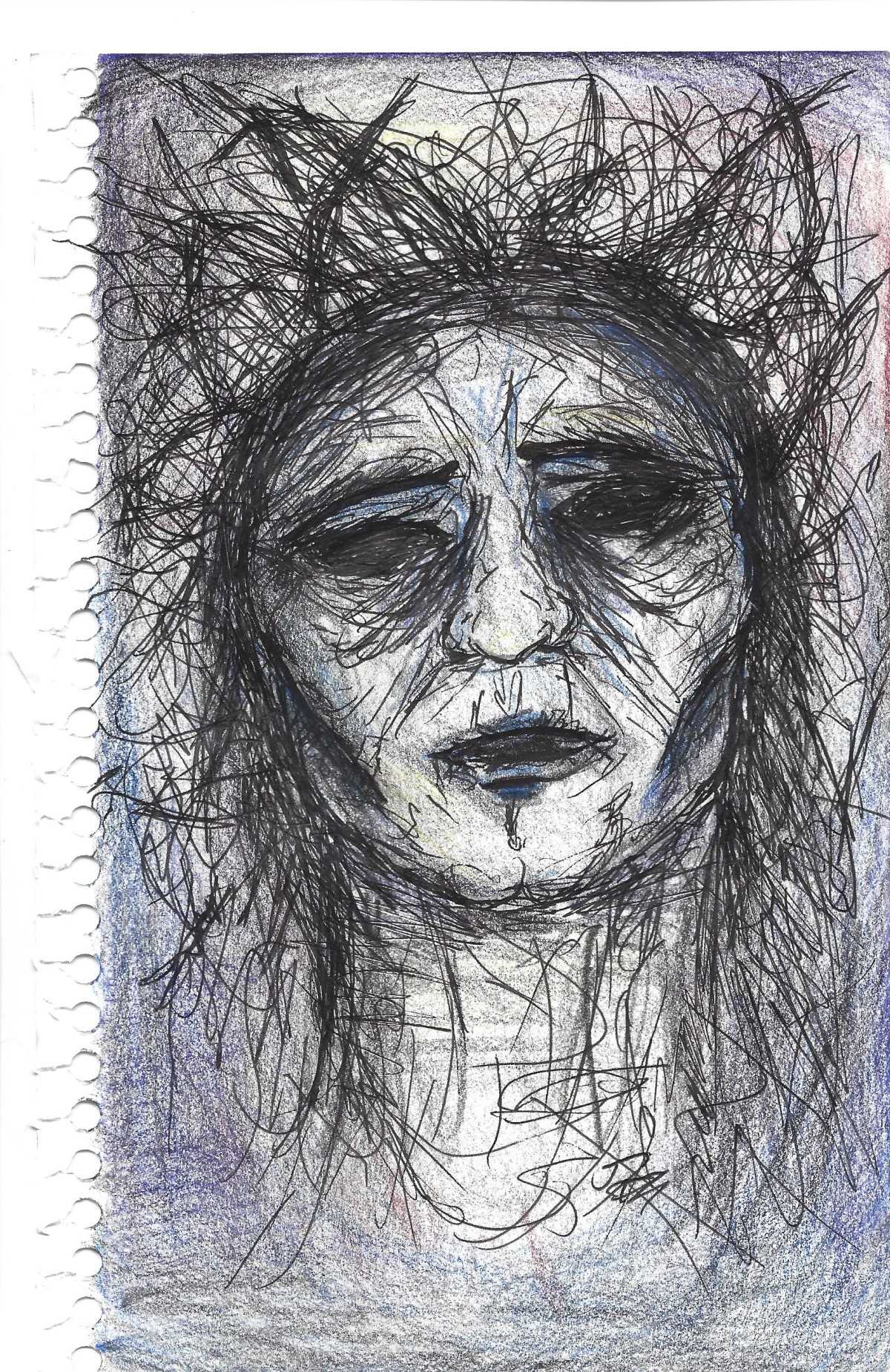

“[I] put on a smile…whereas on the inside, it’s a dark, dark valley,” Jessica said.

Jessica is diagnosed with clinical depression, and she is not alone. In fact, she is joined by 30 percent of students in Fairfax County public high schools. It’s a shocking number, there is no doubt about that. However, what’s more disturbing than that statistic is what depression is doing to our school and its students.

In order to fully understand the gravity of what students with depression deal with, it is important to understand what depression is.

While depression may seem like it’s primarily an emotional issue, it is often caused by chemical imbalances in the brain. Everyone has neurotransmitters that send messages throughout the brain. Too much or too little of a certain chemical or neurotransmitter can often result in mild to severe depression. For instance, too much of the neurotransmitter Acetylcholine, which is associated with recollection and memory, can lead to depression. Too little Seratonin, a neurotransmitter that affects mood, also leads to depression. Norepinephrine controls things like blood pressure. Too much can lead to anxiety as well as certain forms of depression. And there are other physical causes. A study in The Journal of Neuroscience showed that of 24 women who had been diagnosed with clinical depression, on average, their hippocampus was nine to 13 percent smaller than average. This study indicates that stress plays a major role in the size of the hippocampus. Stress can suppress the production of neuron cells in the hippocampus, which is crucial to short-term and long-term memory.

Depression is often beyond the control of those who suffer from it. In many cases, psychiatrists and doctors prescribe drugs that can help address these chemical imbalances.

That being said, in many cases the problem is not purely chemical. In a key study of depression done by psychologists M.E.P Seligman and S.F Maier in 1967, they discovered that a major source of depression is a sense of futility, what they called “learned helplessness.” In this study, dogs were subjected to minor electrical shocks. Some dogs were allowed to avoid the shocks by moving their heads, while others could do nothing to prevent the shocks. Eventually, the latter group gave up and simply became resigned to their suffering. The concept of learned helplessness is that repeated failure just leads to people giving up.

This problem is all too familiar with high school students, especially with the high expectations of parents, teachers and colleges. With so much pressure on students, it’s not surprising that there are times when they feel that no matter how hard they try, they cannot succeed. Add to that the pressures of high school social life, in which many may feel ostracized by their community, and there is a recipe for disaster and severe mental issues.

“I see a lot of kids who have symptoms of depression as well as high levels of anxiety,” school psychologist Beth Werfel said. “And a lot of times, the anxiety come first…then it just spirals down and then the depression latches on.”

“It’s just too much,” an anonymous junior said. “We have too many expectations weighing us down.

It would also seem that an equal amount of pressure come from those around a person.

“It’s the mindset that convinces me that I have to do everything right,” Jessica said. “The thought that everyone is against me, that really fuels the anxiety.”

In addition to the difficulty that comes with fitting in, an even more difficult challenge is getting other people to understand depression.

“Talking with someone who understands depression is very helpful and can change someone’s way of being dramatically,” an anonymous junior said.

However, it is not easy to find someone who understands, and even if one does, it is still hard to be open with them.

“The problem is that the stigma is hard to overcome,” senior Jack Saunders said. “It’s so important to talk to people about it but it’s really difficult for some kids.”

Saunders was recently the keynote speaker at the Joshua Ball in Arlington on Oct. 23. The Joshua Ball is a fundraiser for the Josh Anderson Foundation, a charity organization whose mission is to provide teens with mental health information. Saunders discussed his personal experiences with depression and gave advice about coping in his speech at the Joshua Ball.

“Discussing my problems was the best way to overcome,” Saunders said.

It’s incredibly hard for people who don’t suffer from depression to understand what those who do are going though. For those who have never felt depression, it is easy to think that the pain of depression is just like any other pain.

I’ve seen firsthand what depression can do to somebody, both at school and in my personal life. It’s a destructive disability, one that can turn the happiest of men into a weary and dejected ruin.

My late grandfather struggled with depression for a good part of his life. I had seen him at his best and his worst, but for some reason I simply didn’t understand why he just couldn’t be happy.

I have begun to understand what my grandfather was dealing with. He once tried to explain to me what it felt like to be depressed. I distinctly remember him describing depression as a hole that he could not get out of.

It’s a common theme among depressed people, the idea of a metaphorical tunnel with no light at the end of it.

“The depression feels like drowning,” Meloy said. “[It’s] like you can’t breathe and you’re underwater, completely helpless.”

What’s worse about depression is being aware of the illness and knowing that the world doesn’t stop to help the depressed cope.

“Yet [while drowning], you can still see everyone else breathing.”

The question that we as a community must now ask ourselves is: What can we do?

There is no doubt that this is a tough question to answer, and Fairfax County has done a good job thus far with educating the public about depression as well as attempting to extinguish the depressive flames that run through our halls.

FCPS has taken steps to combat depression in recent years. With the addition of suicide hotlines and depression detection tactics to the FCPS website, it is clear that FCPS has taken steps to ensure the safety of students in our county.

While the county as a whole has seemingly done an impressive job to increase awareness, some students feel that more measures could be taken.

“I feel like McLean as a school has done an excellent job, but I think that the county could be doing more,” Saunders said.

McLean High School has also begun to take serious measures to address the problem of depression.

Between Nov. 10 and 19 of this year, all freshmen were required to go through the Acknowledge, Care, and Tell Program.

“This program teaches students signs of depression as well as how to get help for themselves or a friend who is exhibiting symptoms of depression,” Director of Student Services Paul Stansbery said. “All freshmen who participate will be given a depression screening tool so that we can follow up with any students in need of assistance now.”

Even though it is clear that the McLean administration is attempting to address the problem, there exists another pressing question: Are we as students doing enough?

Students are beginning to speak out on the topic of depression. Those who are suffering from depression are helping the rest understand what they’re going through so that we all can be more supportive. These students are also looking to help other students cope with their pain.

“I want people to know that they can come to me for advice,” Meloy said. When asked why she decided to decline the option to remain anonymous, she replied, “I have nothing to hide. I am not ashamed. I want to let others know that it’s okay to do the same.”

We have a long way to go as a community in helping people deal with their depression, but we are making progress. Jessica has learned how to cope better, and while she has a ways to go, things seem bright for the future.

“I consider it a success story,” she said.