Trigger warning: this article discusses sensitive topics, including sexual assault and abuse, which may be distressing for some readers.

Senior Ariana* was only 13 when she was sexually assaulted by her boyfriend.

Sexual assault isn’t always a violent act committed by a stranger in a dark alley—it often happens in the supposed “safe zone” of a relationship. But many teens don’t perceive it for what it is. Being in a relationship doesn’t mean automatic consent. Coercion—even from a partner—is abuse.

If conversations on the subject of abuse happen at all, they are usually centered around highly publicized cases involving prominent figures. The more insidious forms of abuse within relationships, like gaslighting, manipulation and pressure to have sex, are often unaddressed. In Ariana’s case, her experience with sexual assault would not have been reported until she found the courage to speak up about her assault by confiding in her therapist.

When alcohol or drugs are involved, the lines are blurred even further. What seems like a consensual decision can quickly devolve into a dangerous situation where one party is powerless. Sexual assaults are often linked to intoxication—according to research published by the National Institute of Health, 50% of sexual assaults involve alcoholic influence.

The fear of losing a relationship, the confusion of what counts as abuse and the tendency to minimize experience contribute to a culture of silence. But silence allows the cycle to continue. It causes victims to question themselves and not their abusers, to internalize shame rather than seek help. It influences partners into believing coercion is normal and that they owe their bodies to someone else.

Silence allows abuse to go unchallenged and unspoken.

Defining Abuse

Abuse within relationships is characterized by a defined power dynamic. Although not all abuse takes the same form, it generally occurs when one person is harmed physically or emotionally. This includes manipulation, gaslighting, pressure to have sex, stalking, sexual assault, verbal harassment, physical abuse, cyberbullying, choking and more. In a survey of 145 McLean students, 16 responders reported that they have experienced sexual assault or rape.

“In abusive relationships, one party has a lot more power than the other party has,” school psychologist Carol Ann Forrest said. “One feels like they have all of the ability to control an interaction, and the other one feels powerless, not able to advocate for themselves.”

Although verbal abuse is generally the most common among teenagers, emotional abuse can often take more complex forms than verbal abuse. Gaslighting, when one person uses lies and pointed remarks to make another feel that their version of reality is false, can be extremely difficult to detect in real life. Forrest estimates that about one in three McLean students in an intimate relationship have undergone some form of emotional manipulation.

Physical and emotional abuse are two distinct categories, but in many real-world cases, both occur simultaneously. McLean junior Beth* described her experience being in a relationship with an 18-year-old at the age of 16. Her then-boyfriend gained her trust, sent her explicit photos and eventually pressured her into having sex.

“If I didn’t say yes…he wouldn’t stop pestering me,” Beth said. “It’s like one of those scam callers [that] won’t leave you alone until you give them what they want.”

Romeo and Juliet laws are in place in Virginia, legally protecting any couple who engages in consensual sex if both parties are aged 15 to 17. Since Beth’s boyfriend had already entered legal adulthood when he had sex with her, he would be legally liable for a Class 1 misdemeanor. Although Beth chose not to press charges, had he been convicted for contributing to the delinquency of a minor, he would have received up to one year in prison and $2,500 in fines.

The Code of Virginia does not include a definition of consent, but it does state that rape occurs if there is “force, threat or intimidation” or if the victim is in a state of “mental incapacity or physical helplessness.”

Intoxication, by inhibiting one’s judgment, can place victims in dangerous situations and lead to sexual assault. Jenna* was sexually assaulted by her boyfriend while she was intoxicated.

“I liked him a lot, and I guess the lines were kind of blurred for me on what counted as something like that and what didn’t because I thought he liked me back,” Jenna said. “Somebody that does that type of stuff doesn’t actually care about you.”

Reporting an instance of sexual assault may result in charges placed on the abuser. Nevertheless, the vast majority of cases do not end up being prosecuted, primarily due to victims choosing not to report their stories to the police. According to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, out of 1,000 sexual assaults that take place, only 310 are reported, and just 25 of the offenders see jail time.

In other words, approximately 98% of people who commit sexual assaults walk free.

While it is generally agreed upon that sexual assault is unacceptable, other forms of physical abuse are not widely regarded by the public as a severe form of violence, despite their dangers. Erotic asphyxiation, when one partner places pressure around the other’s neck, is becoming a more common practice and is prevalent in the media. It can cause severe long-term brain damage to the victim and is considered a form of physical abuse when non-consensual. Despite its appearances in pornography and television, choking is not acceptable if it is not consented to. Giving permission to have sex does not imply consent to any of these forms of violence.

A survey conducted by the National Institutes of Health reported that 3% of those who have been choked experience losing consciousness and 15% experienced neck bruising.

Beyond the Headlines

Three men were convicted in 2023 for exploiting women in a Tysons prostitution ring. In August 2024, Langley High School teacher David Murray was arrested for sending sexual text messages to a detective he thought was a 15-year-old girl. Just two months later, Langley instructional assistant David Scalea was arrested on charges of sexual misconduct around minors–masturbating under his desk in a classroom. Most recently, in February 2025, Fairview Elementary School teacher John Barger was arrested for allegedly sexually assaulting two students, days before Falls Church High School teacher Richard Berkowitz was arrested for allegedly seeking online sexual acts from minors.

These recent crimes have drawn significant community attention, reinforcing the reality that despite Fairfax County’s apparent safety and affluence, students must remain cautious. Although such cases are generally condemned as legally and morally wrong, they don’t reflect students’ more ambiguous struggles. The contrast between extreme, publicized cases and personal experiences of abuse in relationships can make it harder for students to recognize and validate their situations.

“I think people think sexual assault is just rape, and anything less than that is not that big of a deal, and you shouldn’t talk about it,” junior Annika Singh said. “But it’s letting those things exist that leads to more serious crimes like rape.”

Recognizing signs of abuse is the first step in addressing these issues, but for many teens in relationships, this can be incredibly difficult. Teens often convince themselves that what they’re going through isn’t “bad enough” to sacrifice their romantic relationship completely.

“[Abuse] can be through touch. It can be through other kinds of sexual means. Sometimes, it’s verbal comments. It doesn’t have to be physical,” school psychologist Beverly Parker-Lewis said. “It is really when any one individual assumes control or power over another with the intent or behaviors that infringe upon a person’s sexual being.”

Especially because of cases of clear power imbalances, like a teacher assaulting a student or men exploiting women in a coercive prostitution ring, students question if the abuse they encounter in a relationship with a partner of similar age or status can be classified under the same level.

“I think, one way or another, there is a power imbalance there,” Ariana said. “Whether it’s real or perceived, it creates this world in which somebody might not feel comfortable speaking up.”

Despite the publicity of crimes against minors, some people still fail to take them seriously.

“I’ve seen people make edits and joke around about the teachers,” said Langley senior Andrew Hwang, a former student of Murray, who was arrested for sexual solicitation of a minor. “It’s definitely a more lighthearted reaction. It’s expected for high schoolers, but I think people should recognize that this is more of a severe issue than they think.”

At a McLean vs. Langley football game on Nov. 8, McLean students encouraged each other to wear Santa hats to the stands, referencing one of Murray’s released text messages in which he inappropriately role-played as Santa Claus. Although the school administration banned the hats, McLean’s pep band played an impromptu “Jingle Bells” performance to mock McLean’s opponents. These reactions counteract a growing societal push for awareness and prevention.

“I don’t think that sexual abuse is more common now, [but] we are more aware,” Parker-Lewis said. “The #MeToo movement that blossomed a few years ago opened people’s minds about their rights, about their bodies, about their protections. It gave them a voice.”

However, these conversations largely don’t apply to abuse in teenage relationships. Unlike clear-cut cases of assault by strangers or authority figures, abuse within a relationship often comes with emotional complications. Young victims may still care about their partner, hold onto memories of when the relationship was “good” or hope that the abusive behavior will change. Saying no can feel impossible when it means defying or disappointing someone they trust or love.

“When you’re feeling really bad, even negative attention is still attention,” Ariana said. “[I felt like] it wasn’t bad enough for me to warrant leaving.”

Even if a victim is ready to leave, reporting the abuse is another daunting challenge. Speaking up about such a deeply personal violation can be terrifying, especially with looming fears of not being believed or facing personal retaliation. The process itself is often long and emotionally taxing, and many survivors worry that even if they do speak out, the repercussions for abusers won’t be enough to prevent future harm.

The lack of harsh consequences can discourage survivors from reporting future incidents, leading to a cycle of silence. Cases that don’t involve physical evidence or clear threats can be difficult to take to trial, stopping victims from pursuing legal action.

“I understand that reporting sexual assault is important, which is why I did it the first few times I’ve been harassed,” Singh said. “But if there are no consequences to it, it’s going to deter everybody from talking about it, especially since it’s already such a difficult thing to talk about.”

Parental awareness also plays a crucial role in prevention and support in personal relationships, yet many parents struggle to recognize the warning signs of dating abuse. According to the Center Against Sexual and Family Violence, 81% of parents do not consider teen dating violence a problem or are not sure. Of these parents, 58% were not able to recognize all the indicators of abuse. These signs—such as emotional manipulation, social isolation and subtle coercion—can go unnoticed, perpetuating the cycle of silence.

Profiles

Jenna

While spending the day at her then boyfriend’s house, McLean student Jenna expected a typical afternoon with someone she trusted. Instead, she was taken advantage of while intoxicated.

“I was drunk because he gave me alcohol and then proceeded to do things,” Jenna said. “He pretended to not know that I was drunk when he was completely sober.”

Despite Jenna’s inability to give clear consent, her boyfriend continued to pressure her into intimacy. Feeling confused and powerless, Jenna struggled to understand what had happened. As she processed her emotions over time, she realized the gravity of the situation.

“Even if you [don’t] directly [say], ‘No, I don’t want to do that,’ it’s still nonconsensual if you’re not saying yes firmly, especially if you’re intoxicated,” Jenna said.

Throughout their relationship, the pattern of manipulation and coercion persisted. When Jenna would express discomfort or decline his advances, her boyfriend would respond with spiteful comments or passive-aggressive behavior, making her feel guilty and pressured to comply.

“I didn’t think much of it until a few months later,” Jenna said. “I was talking with one of my friends about what happened, and they told me [it was] messed up and that I should tell somebody about it.”

A friend encouraged Jenna to confide in a trusted adult, hoping for understanding and support. Instead, she was met with indifference.

“I’ve tried to speak up to [an] adult before, and they didn’t do much,” Jenna said. “At that point, I [felt] like I’d rather just keep it to myself.”

The lack of support kept her from disclosing the incident, as she believed it wasn’t significant enough to warrant a report. Over time, Jenna began to understand the weight of her experience and felt the regret of not speaking out sooner. She realized that the judgment of others often passes and is rooted in ignorance.

“If it gets out and people start talking about you or looking at you in a negative light, don’t worry about it, because it’ll pass,” Jenna said. “It’s just people being stupid. They’re most likely ignorant if they’re just going to judge you for something that’s not your fault.”

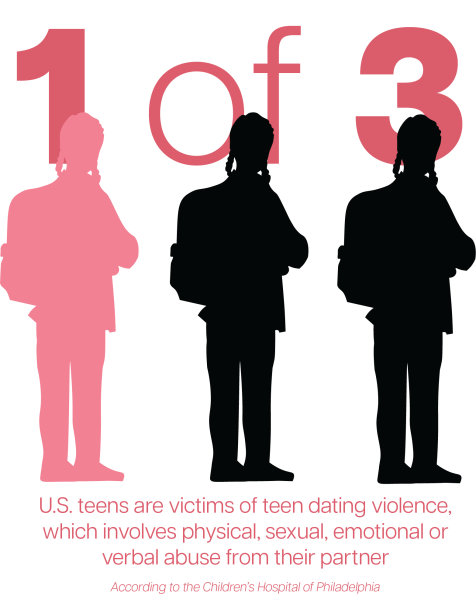

Jenna’s story is not an isolated incident. Contradicting the social stereotypes that purport abuse to be rare, the American Psychological Association states that about one in every three teens has experienced dating violence.

“Honestly, a lot of people just need to wake up and realize that it happens all the time. It’s way more common than you think,” Jenna said.

For victims who choose to share their experiences, genuine empathy and active listening can provide crucial support.

“You can’t just listen to somebody but not hear what they’re saying,” Jenna said. “If more people truly listened [and] took into account what victims have come out and said, actual change would be able to happen. But nobody listens to it sincerely.”

Jenna’s past has caused her to approach relationships with greater caution, even with those she loves and relies on.

“Be careful of who you trust. Always make sure you know the person before doing anything with them,” Jenna said. “If you’re not completely sure about it, just wait. Waiting has no horrible repercussions on you. If they don’t want to wait for you, then you’re avoiding a terrible person.”

Ariana

When Ariana was assaulted for the first time in eighth grade, she was dating a high school sophomore. The assault was reported to the police by her therapist, who encouraged her to communicate with the authorities and her family.

“One of the most harrowing parts about it was needing to have the therapist tell my mom we have to go to the police station [and] make a report,” Ariana said.

At the police station, Ariana was brought into an interview room. There, officers questioned her about her assaulter’s description.

“It was weird [and] very awkward going into the details that the officer was asking for with my mom there,” Ariana said. “But my mom was very supportive of me after she figured that out, which I’m grateful for.”

In Virginia, a parent or guardian is required to be notified when a minor is involved in legal proceedings regarding sexual assault.

“I was 13 years old, so I can understand why I needed a parent present,” Ariana said. “It made talking to the officer a lot easier because there is no way that I would have [gone] and told my parents out of my own volition.”

Had Ariana’s therapist not reported the assault, Ariana is certain she would not have told her parents about it.

“I had avoided telling my parents about that sort of stuff. I grew up in a house where anything sex is [extremely] taboo,” Ariana said. “It’s not a very open household. So I was used to keeping a lot of things to myself.”

Even outside her home, Ariana struggled to speak up due to the social stigma around conversations about sexual assault.

“There is a big culture of shame,” Ariana said. “There’s not much understanding or sympathy, and that can make it difficult to speak out.”

According to a survey conducted by the National Sexual Violence Resource Center, among 51.1% of women who are victims of rape, the perpetrator was their partner. Many victims never report their assaults as they feel the police will not address their cases adequately.

“Nothing came of it when I went to the police. Even if I had pressed charges, I wouldn’t have expected [them to do anything],” Ariana said. “It’s not that I lost faith in the system—I just never really had it to begin with.”

The second time Ariana was taken advantage of was by another boyfriend in her freshman year of high school. Before she was assaulted, Ariana was given cannabis edibles by her boyfriend.

“I remember looking him in the eyes [and saying], ‘I do not want to do anything when I am trying these,’” Ariana said.

Despite her clear expression of discomfort, the pressure she felt in the relationship overpowered her boundaries.

“There was a power imbalance in those relationships because I was so attached,” Ariana said. “I was very afraid of losing them. So I felt as if it was something that I had to do.”

Her toxic relationships led Ariana to compromise her own sense of security and prioritize pleasing those she trusted.

“In my rational brain, I can recognize that most men do not pose a threat, but because of the experiences that I had, I get very anxious,” Ariana said.

Though these past experiences have left Ariana with lasting anxiety, they also taught her the importance of confiding in at least one trusted person for support.

“The vast majority of people will support you and listen. Even if you know the authorities might not help you, other people will listen to you,” Ariana said. “And if they don’t, it’s a reflection on them more than it is you.”

Beth

Beth experienced sexual coercion and harassment at the hands of her boyfriend, a legal adult.

The two met through a mutual friend and began talking shortly after. After a few weeks of flirty text messages, he asked her to start a relationship with him. She was 16 and he was 18.

“At first, he was very attentive. [He was] like, ‘Oh, have you eaten today?’ ‘Are you busy?’ ‘Do you want to hang out?’” Beth said. “Two weeks after that, he started pressing me about sleeping with him.”

Beth’s boyfriend sent her unsolicited nude pictures despite her repeatedly telling him to stop, and he requested she send back her own. She refused.

“He wouldn’t take no for an answer. He would let it calm down for a few days and then try again, even after I explained [that] I don’t want this because once you send someone your photo, you don’t know what they’re going to do with it,” Beth said.

Despite her discomfort, Beth began wondering if their relationship would return to normal if she fulfilled his requests.

“I think I just got blinded by the fact of ‘what if,’” Beth said. “What if he’d go back to the way he was during the first couple weeks of us talking? What if I just agree and he’ll go back to normal?”

Beth eventually had sex with him. She describes her consent as “reluctant agreement.”

“I realized halfway through. I was like, ‘I can’t do this,’” Beth said. “I made up an excuse about my mom wanting me home and I just left.”

Beth felt trapped. At one point, he threatened to kill her when she tried to break up with him. By confiding in her mom, Beth was able to escape the situation and heal.

“[My mom] was not disappointed, but more in shock that I hadn’t told her before, because at this point, I needed to get out more than anything. And in the end, she was willing to help me,” Beth said. “I think it was just the fear of judgment that stopped me for so long.”

After her boyfriend went to college, Beth broke up with him through text. Using resources provided by her therapist, Beth was able to heal from the situation. Beth no longer has any contact with her former boyfriend, though she worries she will run into him one day.

Even though her boyfriend coerced her into having sex as a legal adult and harassed her over a period of time, Beth did not press charges due to her disillusionment with the length of time it takes for legal action to occur and a concern that the harassment charges would only yield a “slap on the wrist.” She worries that talking to the police and moving forward with a lawsuit will cause the stress of the situation to resurface.

“I just really don’t want to see him again,” Beth said. “I don’t want to relive it.”

Resources and Recovery

Support is necessary to overcome sexual abuse. Abuse within relationships, particularly, can be even more challenging to address. Raising awareness and providing resources for those in such situations is crucial for helping victims heal and break the cycle.

McLean offers a network of counselors, psychologists and social workers to help students navigate challenging situations. These specialists are available to provide guidance and emotional support during traumatic incidents.

“We have two psychologists and one social worker. We also have nine counselors and a counselor supervisor who are also able to provide supportive information for students. We can provide [students] with counseling support,” Parker-Lewis said.

Although there are limits to what McLean’s student services can provide, they can still be a starting point for students seeking help.

“We don’t do therapy, but if it appears that the student is in need of therapeutic support that’s much more than what we’re providing here, then we support the student and the family in trying to help them identify resources in the community that can provide that kind of ongoing assistance,” Parker-Lewis said.

In the case that legal action is needed, students at McLean can make a report to the School Resource Officer (SRO). The SRO can take reports at any time, regardless of when the incident occurs.

“Officer Scott Davis is here to guide us through that process. He’s great support for us when we see that something may need legal support. He can talk to us about what needs to be done [and] who to contact,” Parker-Lewis said.

Conversations about practicing safe sex can be necessary in preventing the abuse. Consistent communication with trusted adults, whether parents, teachers or counselors, creates a foundation for students to seek help when needed. When those discussions happen before a crisis arises, it becomes easier for teens to recognize warning signs and advocate for themselves.

“When I gave birth to my daughter, I had to educate her on protecting herself. From the time she was 2 years old, we identified private parts and [talked] about people not invading personal space, learning how to say no and knowing how to have a loud voice to advocate for yourself,” school social worker Marly Jerome-Featherson said.

Rhetoric plays a powerful role in influencing how abuse is perceived because perpetrators often verbally manipulate victims into believing that it’s not abuse. Creating spaces where the experience of victims is acknowledged and validated is necessary to reverse that.

“If [victims] can be heard, then that allows them to step forward or confide in somebody else who can support them,” Parker-Lewis said. “We need to approach these conversations with good, factual information. Having information available is an important piece. It’s not a question of ‘Has it become more prevalent?’ Wherever harassment is happening, if it’s occurring, it’s too prevalent.”

*The names Ariana, Beth and Jenna are pseudonyms to protect their identities.

If you have experienced domestic violence, sexual assault or another form of abuse, the following phone numbers may provide some assistance.

1.800.799.SAFE (7233) (domestic violence hotline)

1.800.656.HOPE (4673) – RAINN (rape, abuse, & incest national network)

703-360-7273 FCPS Domestic and Sexual Violence hotline