Senior Polina Zubarev* had a sore throat. She was tired. She had a headache. Her first symptoms were mild but soon worsened, prompting her to take a COVID-19 test. It came back positive.

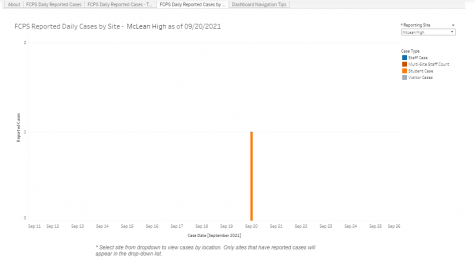

But despite promptly notifying the school on Thursday, Sept. 16, and answering McLean Assistant Principal Sean Rolon’s questions over the phone, the case never appeared on the Fairfax County Public Schools (FCPS) 2021-22 COVID-19 case dashboard, and no teachers or students were notified about potential exposure.

Contact tracing and case reporting do not occur for students who were not infectious on-site. According to CDC guidelines referenced on an FCPS Guidance page, the infectious period for symptomatic cases begins “two days before illness onset.” For Zubarev, the infectious period began on Thursday, Sept. 9, since her symptoms began on Saturday, Sept. 11—meaning she spent Thursday and Friday as an infectious case on school grounds.

“The public health guidance that we get, also based on CDC guidance, is that if [the students] were not on-site when they were infectious, then the [Fairfax County] Health Department determines there are not any public health actions that are [needed],” said Lea Skurpski, FCPS Director of Operations and Public Planning.

When a staff member, student or visitor tests positive for COVID-19 and informs the school, a rapid process is supposed to take place; an administrator fills out paperwork, then reports it to the Fairfax County Department of Health.

“FCPS reports cases to the Health Department,” Skurpski said. “As soon as they do that, all potential close contacts receive a communication…and the [contact tracing] process begins.”

Teachers and students are tracked based on seating charts stored at the front office, according to Principal Ellen Reilly. It is then the Health Department’s job to contact families and determine who is a close contact.

“[When we] provide a list of potential close contacts, [the Health Department is] going to communicate with the ones that they deem high risk,” assistant principal Rolon said. “They get that information from us, then they determine who they’re going to reach out to…When an investigation is complete, they will send us a clearance letter that just states all students are cleared.”

But in Polina’s case, since she was erroneously deemed not infectious on-site, nothing happened.

“It wasn’t really clear that they got the message [I was positive],” Zubarev said. “It wasn’t put up on the FCPS COVID-19 tracking website at all…even though we had reported it…so on Thursday [Sept. 16, the day I notified the school] and Friday [Sept. 17], nothing goes up yet, which was a little surprising, and none of my teachers knew either.”

One student was questioned by the Health Department about possible symptoms, but immediately after his mother was called and informed that there was no positive case at school. Rolon believes this was a slip-up at the Health Department, indicating critical issues with the bureaucratic, complex case reporting process.

“I think [that was] unauthorized communication that went out from the Health Department,” Rolon said. “ I do know that they’re trying their very best, but there’s a pretty decent sized backlog, and they’re working through them.”

Another student, senior Tommy Lizzaralde, learned about Zubarev’s case on Thursday, Sept. 16 through personal messages with her, not a school official. He tested negative after frantically searching for a COVID-19 test on short notice.

“We could have inadvertently spread infection in our community, and in Maryland when we went to visit our older son, as we probably would have been asymptomatic,” said Mary Gramiglia, Lizzaralde’s mother. “The school needs to be completely upfront with all parents and should report infections on a weekly basis.”

Another student, senior Collin Coerr, was notified about Polina’s case on September 29, 13 days after Polina notified the school and after being cleared to return to school.

“[The school] made a quick phone call to my mother…informing her that I was meant to be quarantining for 10 days, starting 15 days ago,” Coerr said. “The school did not tell me or my family anything during the period while she was in school…based on my experiences with Polina’s case, this ‘system’ does not work well at all.”

But even when an individual is successfully reported on the tracking website, actually notifying the community can take multiple days. After an on-site infectious case from Sept. 20 was reported, Reilly’s message to the community didn’t go out until Sept. 24. Knowing that cases exist in the school affects how people behave on campus—some students now claim to be more careful with distancing, for instance—so timing is crucial to public perception and outbreak prevention.

“I currently don’t trust FCPS and the school because they took so long to tell us,” senior Gianna Di-Reumante said. “It’s a shame because in this way it seems like they don’t necessarily care much for our well-being but rather that we stay in school.”

Zubarev, too, said she thinks the school and FCPS need to be more transparent with staff and students.

“I just wish that the school would be a little bit more on top of things, because as far as I know…I’m one of the few people who’s even [gotten COVID-19] at McLean,” Zubarev said. “So I think it’s not that hard to at least contact teachers and let them know what happened.”

*Polina Zubarev is a managing editor for The Highlander.

Additional reporting by Maya Amman.