In subject areas with a focus on obtaining factual knowledge like history or science, there are strict county and state standards, making it difficult for there to be variability in course assignments or materials.

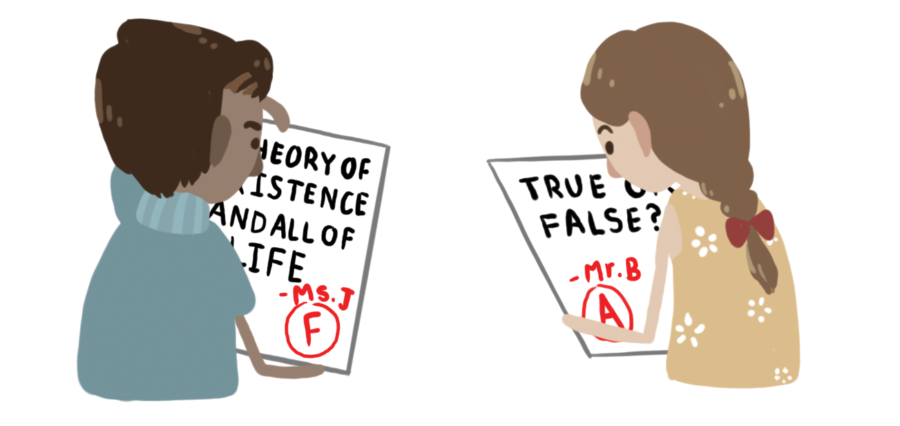

However, subjects like English or foreign languages have flexible curriculums due to broad standards of learning. They also leave room for subjectivity in grading criteria. This can become problematic for students, as a difference in grading standards can at times be unfairly advantageous or disadvantageous.

A course requirement for a 9th grade English class in FCPS may be, “students must have read Romeo and Juliet,” or “students must know how to construct a thesis statement.” In a chemistry class, however, a requirement may be, “students must be able to correctly use and apply the ideal gas law with an understanding of Avogadro’s constant.”

Though both courses have standards of learning, that of chemistry is much more specific and restrained than that of English.

“[The standards of learning] are not specific enough in some cases. It’s too loosey-goosey. There’s a lack of clarity about what we are supposed to be focusing on,” English department chair Susan Copsey said. “For example, English 12 has traditionally been a course that’s just so broad. ‘British literature and the literature of other cultures’—I mean, that basically means we can teach anything.”

Although students are aware that different teachers may have their own unique teaching styles, when students sign up for the same course, they generally expect to receive the same education, including the standards by which they are to be graded.

“I agree it’s fairly difficult to maintain the same curriculum throughout all the classes, but it’s still unfair. Based on my experience, a student’s grade fluctuates solely based on the teacher,” senior Joy Kim said.

A common argument against a uniform curriculum is that teachers should be able to choose what they wish to teach their students based on what they believe is most important to their education.

“If someone is telling me what to teach every single day, then that kills the joy of teaching,” Copsey said.

According to the Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, “When a [teacher] becomes involved in planning the curriculum for the students he is to teach, he has a personal stake in the matter and usually does a better job of teaching.”

Although this is a valid statement, it only truly holds under the assumption that students are placed in a setting where they are learning for the sake of learning. In the modern world—and especially in McLean—where competition is fiercer than ever, education has become a requirement.

Today, students are merely represented by grades and numerical scores in order to differentiate between the academically skilled and lacking. If there is no set standard, the purpose of a grade will have been defeated. In order for there to be a comparison, there must be controls.

These controls must stem from a uniform curriculum and a common grading standard that can be used across all classes of the same course. For the sake of fairness, every student should be evaluated using the same guidelines for the same assignments and assessments.

The English department has made considerable strides toward providing students a more equitable high school experience.

“Five years ago, teachers would go in [their] rooms, shut the door and do their own darn thing. You would see such a wide disparity,” Copsey said. “[Now], the movement toward the Professional Learning Community model has eliminated many of [those discrepancies].”

It is reasonable to infer that a completely uniform curriculum will not ever be feasible. However, so long as academic competition remains a driving force for education, teachers must endeavor to approach a common, coordinated curriculum.