In the midst of the 20th century, three Nike missile defense installation sites were built in the Fairfax region. The government distributed over 400 million forms of media alerting citizens to stockpile food and construct fallout shelters; the government created a distinctive Northern Virginia-specific evacuation plan as citizens grew paranoid in an atomic age. Fairfax County’s proximity to Washington D.C. made it a hotspot for strategic Cold War developments.

1957-1958

When the Soviet Union launched Sputnik–the first man-made satellite–into Earth’s orbit in 1957, it catapulted the arms race to new heights and ignited the space race. As American paranoia proliferated, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the National Defense Education Act (NDEA), which pushed public schools to prioritize STEM disciplines. In doing so he hoped to cultivate the next generation of skilled scientists and engineers to compete with the Soviets.

1960s

The direct impacts of the NDEA were felt in FCPS with the sudden introduction of the School Mathematics Study Group (SMSG). Receiving over $10M in federal funding, the think tank worked to rework and enhance K-12 math curriculums across the nation. Funds from the NDEA were also allocated across various FCPS campuses including Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology and Woodson High School. The FCPS program was a success and by the end of the decade, nine different planetariums had been built.

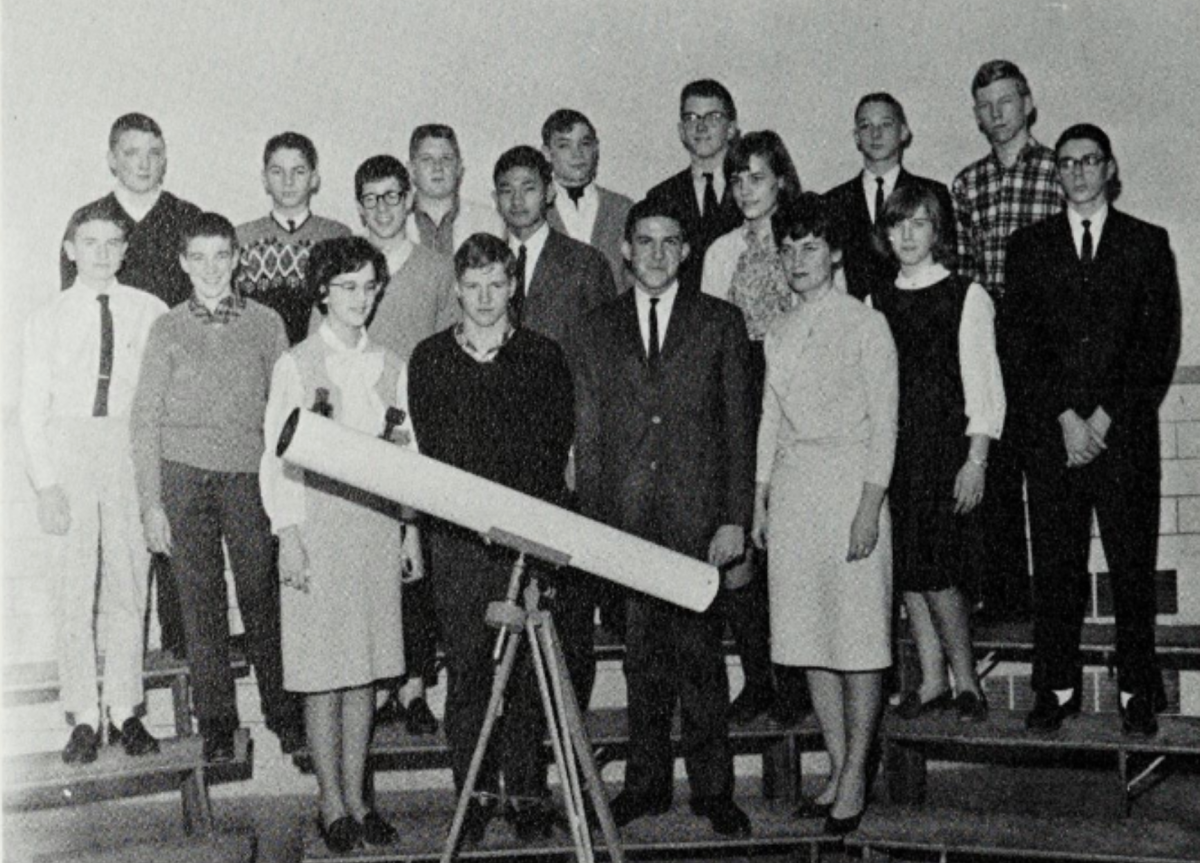

1963

Amidst the talk of astronomy educational enrichment developments in Fairfax County, the McLean Astronomy Club was formed in 1962 to “further interest in astronomy in the area and provide opportunities for observation of celestial objects and their movements.” The following year students and then Astronomy Club sponsor, Johanna Donaldson, began plans to build an observatory. The student-led project was completed in 1965.

From McLean Suburbia to the Stars: William F. Readdy

William F. Readdy graduated as part of McLean’s class of 1970, twenty-two years later, he boarded the Discovery Space Shuttle bound for Low Earth Orbit, becoming the first and only McLean alum to become an astronaut. Growing up amid the space race, Readdy’s career was inspired by the great astronautical advancements of the era.

“When we were going to high school we were flying into space and landing on the Moon for the first time,” Readdy said. “I decided when I was in high school that [pursuing the field of aeronautics and space] was something I wanted to do.”

At the time, FCPS emphasized STEM education under the NDEA, yet McLean also housed a unique World Civilizations course for juniors. Enrolled students explored a well-rounded and international social studies education–Russian literature and language, Western European history and culture–with a mid-year trip to the USSR. Readdy credits the World Civilizations class for influencing his view on international relations, which he would later channel through his career collaborating with foreign astronauts and promoting diplomacy in space.

“I think the course was a great way to be taught and I felt like I had kind of a head-start in life: I had already been to the USSR and exposed to the complex cultural differences and what not,” Readdy said. “While I was going through the naval academy and everything else, the Soviet Union were the ‘bad guys,’ they were our adversaries. I got to be in charge of the effort to bring the USSR to the international space station, and now they’re our partner along with 30 other international agencies. It demonstrated that we can be friends even though we have different political interests and forms of government.”

Readdy received his degree in Aerospace Engineering from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1974. He then joined naval aviation and was deployed to the Caribbean and Mediterranean in the USS Coral Sea (an aircraft carrier ship also known as the “ageless carrier”). He transferred to NASA in 1986 leading various efforts and logging 672 hours in space across three different Space Shuttle missions.

“When you look out the window at the Earth, your first impression is that there's only one continent, one ocean, one atmosphere. As you soar over the Earth there are things that you see and things that you don’t see: you see the majesty of the Earth, all the different wonders–snow and ice–but what you don’t see are any language barriers, cultural differences, or international boundaries,” Readdy said. “It's one of those things when you come back you can’t ever forget.”

Present-day

Decades after the Cold War era, the remnants of FCPS educational developments in the face of the space race prevailed. Among the nine planetariums built by FCPS, only three shut down by the 2010s. However, they are threatened by budget cuts, fewer faculty members who know how to operate the technology, and a general decrease in community interest. In the face of these challenges, physics teacher Dean Howarth took action.

“When I first arrived here in 2011, [the observatory] was out there but it wasn't operational, the electrical system was a mess and to my understanding FCPS was planning to tear it down,” said physics and astronomy teacher Jeff Brocketi. “[Howarth] was really the one who spearheaded the effort to get the county onboard with refurbishing it.”

When Howarth retired after 31 years of working as a teacher, the McLean observatory was formally renamed the Howarth Observatory to honor his contributions to the observatory.

The Astronomy Club also exists to this day and continues to promote the learning and engagement of the cosmos.

“The Astronomy Club invited students to explore the universe through engaging activities and discussions. Members participate in presentations, scientific projects, and host monthly observatory nights,” said Astronomy Club co-president John Chee. “Space really is the future and it’s important to get the youth and community interested and excited for the cosmos.”