As they near legal adulthood, Korean American male students face a challenging decision: retain their Korean citizenship for a future of military service or embrace American citizenship. These students must weigh their options before turning 18, a choice heavily influenced by South Korea’s ongoing ceasefire and mandatory military enlistment.

Although the Korean War is considered to have ended in 1953, the Korean peninsula is still recognized to be in an ongoing conflict. As a result, South Korea’s military conscripts male citizens between the ages of 18 and 28 for 18 months.

Northern Virginia boasts a high Korean population, with the 2010 census recording 41,000 Koreans living in Fairfax County. Since then, the county’s Korean American population has only grown. Many Korean immigrants are drawn to start families and settle in suburban areas like Fairfax County, leading to a dilemma for their Korean American children.

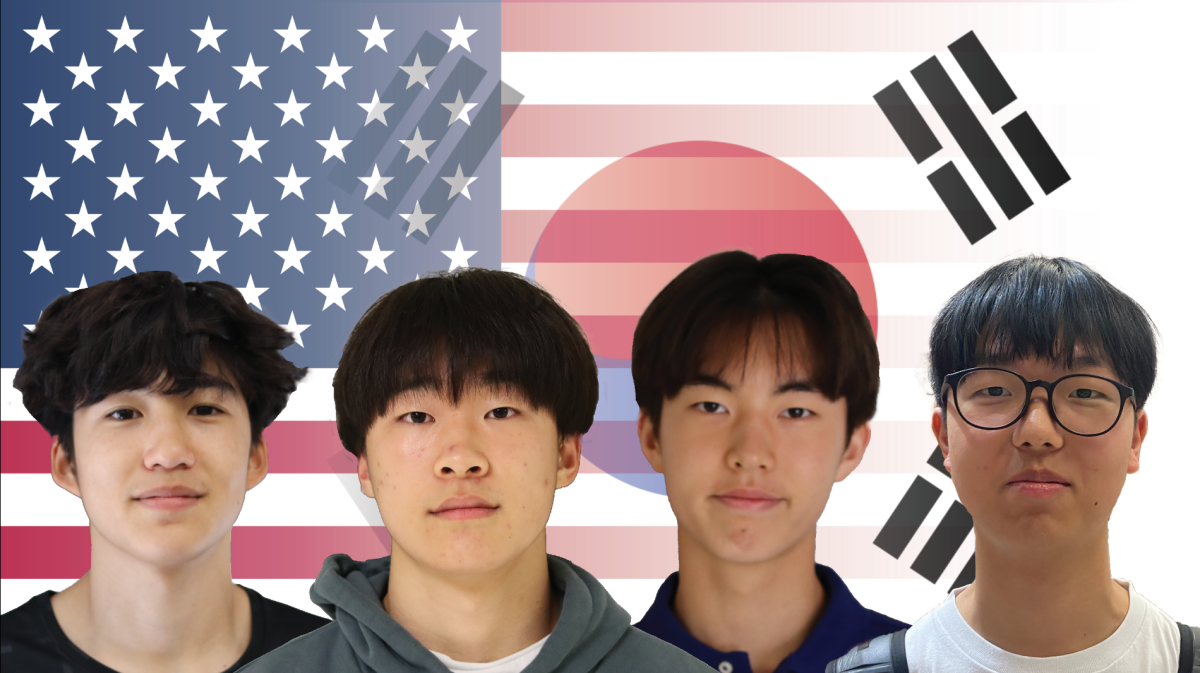

Junior Nathan Park recently renounced his Korean citizenship in advance of turning 18 in his senior year. With two Korean parents, Nathan became the first person in his family to renounce his citizenship and become fully American.

“I went to the Korean embassy and filled out a ton of paperwork,” Nathan said. “I signed whatever my parents gave me to sign and it took a long time to process.”

Nathan remains uncertain about his citizenship renouncement, as he had a short window of time to decide his future.

“I never gave it much thought until it happened, and I felt a little regretful. It would be cool [to keep citizenship] to live in Korea for some time and go back to the country whenever I wanted to,” Nathan said.

The potential risks involved with military service prompted Nathan’s decision to commit to his U.S. citizenship.

“It’s hard to imagine what the military would actually be like,” Nathan Park said. “Coming back to America [after two years] and seeing everyone already ahead of you would be a mental setback.”

Korean Americans often follow the same path as Nathan, since many have lived their entire lives in the U.S. Among these students is junior Colin Park.

“I [chose my American citizenship] because I wasn’t born in Korea, and I don’t have that connection to the country,” Colin said. “It’s a little sad giving away part of my identity, but the exchange for the draft is [acceptable], because I don’t have that same connection to Korea.”

Both Nathan and Colin saw choosing an American citizenship as the only feasible option for them.

“It’s not that I’m unpatriotic, but I always thought that since I was already in America I would stay here because I already have everything here,” Nathan said.

Failing to renounce Korean citizenship before the age of 18 can have consequences that last for years. Under Korean law, avoiding military service is considered a crime.

“My dad sort of had plans of going to the military, but he skipped, so he was [considered] a fugitive,” Colin said. “One time when he went alone to Korea they arrested him and he was about to go on trial. We got lawyers, and everything was resolved. Now he lives in Korea.”

Some Korean Americans believe that the responsibility of service is unfairly imposed, as they don’t share the benefits of citizenship that regular Korean citizens have.

“I guess it’s a little selfish, but I wasn’t even born in Korea,” Colin said. “Koreans live there, so they should be protecting their land.”

On the other hand, there are Korean students who do not hold American citizenship and attend McLean because of their parents’ jobs or for the experience of an American high school. Obtaining American citizenship is a difficult and lengthy process, resulting in most of these students simply maintaining their Korean citizenship.

Senior Woohyun Cho is the activity leader of McLean’s Korean Club. Cho stays in the U.S. through his parent’s work visa. Though Cho is in the process of registering for a green card, due to the unlikelihood of his green card being approved before graduation, Cho plans to live in Korea after high school.

“I’m planning on serving in my second year of university, but I have some concerns about returning back to school after serving,” Cho said. “Going back into society might be a challenge. Sometimes soldiers might sustain injuries while serving, which if it happens to me, [it] might hurt me when I go back to school.”

While Cho has concerns about his military service, he acknowledges that all Korean males undergo the same difficulties. With this being the norm, Korean society holds negative sentiment towards native Koreans who avoid military service. The exceptions are those with mental or physical disabilities that prevent them from serving.

“There’s a lot of public stigma around men who try not to go to the military using illegal [measures],” Cho said. “There was a Korean celebrity, Yoo Seung-jun, who ran away for an American citizenship to avoid going to the military. Most Koreans now hate him and consider him a fake Korean.”

While the common method of citizenship renouncement is a legal process, Korean society views those who go through with it as disloyal citizens. With this public stigma, it is difficult for Koreans who have not served to find employment, another challenge Korean American students must factor into their decision before they turn 18.

“In some cases, military experiences can be helpful in promotion,” Cho said. “Old people love people who went to the military because they share their experiences.”

In addition, Korean culture for males largely revolves around their military service. Those who do not serve often feel alienated from society.

“A lot of the culture among guys [is] centered around the military, especially when drinking and in other [social scenes],” Cho said. “Many Korean men also learn basic skills in the military. They learn [life] skills such as first-aid training, and it is one of the benefits that can be used outside of the military.”

Attitudes regarding those who do not serve differ significantly between Koreans and Korean Americans, often resulting in more uncertainty for those with limited time to make a commitment.

“In Korea, I think the mindset is [of] shame, especially for big celebrities who have skipped and act like they went,” Colin said. “Koreans in America, however, think you did a good job of skipping the military.”

For sophomore Sean Chee, who is currently conflicted between retaining or renouncing his Korean citizenship, many of these issues factor into his decision.

“I’ve been debating about it. I don’t want to just fly to Korea and waste my time for two years, but nothing is certain right now,” Chee said.

The identities of Korean Americans aren’t defined through the paperwork. The experience of growing up in a Korean family remains with these students regardless of their decisions in citizenship status.

“I’m still Korean,” Nathan said. “I’m just no longer an official Korean citizen.”

anna SONG • Aug 19, 2024 at 6:37 pm

In realms of ink where thoughtful voices blend,

A tale of commitment shines so bright and clear.

The Highlander’s article does transcend,

To paint a picture we hold ever dear.

Through vivid prose, a journey we explore,

To Korea’s land, where duty meets with grace.

The writer’s craft opens an earnest door,

And leads us through each chapter, time and place.

With empathy and insight deftly shown,

The narrative unfolds with strength and might.

It speaks of bonds, of heart and spirit known,

In service true, where honor finds its light.

So let this piece, with praise, be rightly crowned,

For in its lines, the depth of heart is found.