In the weeks after the tech company OpenAI released ChatGPT late last school year, students and teachers were awestruck. They rushed to the program, watching in disbelief as the bot responded to their prompts with frightening, human-like outputs. Then, as curiosity turned to realization of its power, students quickly began to assess the chatbot’s ability to complete their schoolwork.

McLean junior Victoria Xiao distinctly remembers how she was introduced to the technology.

“I first heard about ChatGPT from students in my English class last school year,” Xiao said. “They were talking about how they were going to use it to write their essays. I didn’t pay attention to it at first, but after seeing so many students using it and talking about it, I created an account to see what the hype was all about.”

Xiao quickly put the tool to the test.

“The first thing I tried with ChatGPT was to test if it was really legit,” Xiao said. “I asked ChatGPT to write a paragraph on a topic and then to solve a math problem.”

Within five days of its release on the morning of Nov. 30, 2022, ChatGPT broke world records, reaching one million active users. By January 2023, it hit 100 million active users, cementing its place as the fastest-growing consumer application in history.

ChatGPT ushered in a revolutionary era in the technology sector with a new set of AI tools called generative AI. In the months following the release of ChatGPT, new AI programs trained on millions of digital assets gained the ability to generate images, text, music, video and other forms of media, all based on text input.

AI, the process by which a machine can mimic any element of human problem solving and intelligence to produce an output, has existed for years in many forms, from social media algorithms to voice-responsive applications like Siri. Now, generative AI is on the rise — specifically, ChatGPT, which gets its name from the neural networks modeled to build the program: Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPT).

Upon release, ChatGPT and its subsequent competitors, including Google’s Bard chatbot, quickly gained traction through unauthorized means in the classroom. Students took advantage of ChatGPT’s ability to write articulate sentences and used it in a multitude of ways, ranging from unethical plagiarism to self-tutoring.

In June 2023, with the school year ending, ChatGPT lost users for the first time. The application boasting an involved student base is unsurprising — generative AI has taken McLean by storm, rocking the foundation of schooling in a single year. Still, this first full school year with ChatGPT is just the beginning of AI’s transformation of education.

Plagiarism: cheating with AI

Students who use AI run into one major problem: chatbots tend to spew false information. Last spring, a court case made headlines after an attorney used ChatGPT to write a brief in a personal injury lawsuit. The attorney was fined after it became clear that almost all of the legal references written with AI were fabricated.

“[Chatbots] simply make up stuff, or ‘hallucinate,’ and their language continues to be quite confident and persuasive,” said George Mason University professor Sanmay Das, co-director of the university’s Center for Advancing Human-Machine Partnership. “This raises serious questions for anyone relying on the outputs of these systems.”

This misinformation flaw stems from the methods used to train chatbots. These bots are trained on internet sources, so when a source inevitably contains inaccuracies, false information is relayed to the user.

“Especially for educational tools or services, we need to monitor AI’s responses to make sure they are correct,” said Yinlin Chen, a professor of computer science at Virginia Tech, who specializes in AI. “We don’t want to use AI tools that produce incorrect information.”

In addition to producing faulty outputs, chatbot-produced work, even when factual, often falls short of academic expectations.

“I find ChatGPT [to be] kind of incomplete because even the prompts I’ve put into it haven’t [produced] what I would consider quality analysis,” English teacher Michael Enos said. “I think it’s still in its stages of development as far as creating quality responses.”

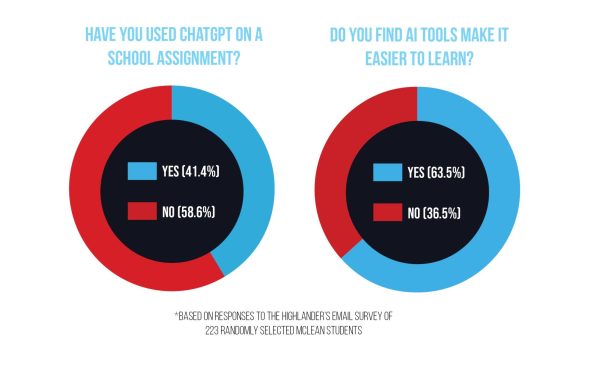

Despite generative AI outputs sometimes falling short of McLean’s academic standard, many students still use AI to complete their school work. In a survey of 223 McLean students, 40% admitted to using AI for at least one school assignment.

“The appeal of ChatGPT [over other cheating methods] is the far lower likelihood of being caught, not because it is hard to notice, but because it is practically impossible to prove for now,” said McLean sophomore John, an alias requested in order for him to speak openly. “Traditional plagiarism has been a problem forever, so very specific methods have been devised to catch it. Generative AI is comparatively very new and is hard to catch by nature.”

Due to rampant low-quality AI responses, some students who have made the choice to use applications like ChatGPT have grown wary of generative AI and are forced to make significant edits to its work.

“The only reason I don’t use it exclusively to do my work is because the output is almost never good enough to get a good grade on writing assignments,” John said. “A teacher suspected I used AI because I didn’t make enough edits to the generated work. I think ChatGPT has a fairly obvious pattern to those who are familiar with it.”

To counter plagiarism issues, several AI companies have been introducing AI detectors. The most notable detector is GPTZero, which despite having a similar name to ChatGPT, is not affiliated with OpenAI. Turnitin, the plagiarism checker used in many school districts, including FCPS, also responded to the cheating crisis with the development of its own AI detection tool.

Turnitin’s AI detector was deemed ineffective this school year, and its development was paused, leaving FCPS teachers without a reliable, county-approved method to identify students who have cheated on assignments with AI.

“The reality of the situation is that with any degree of reliability, it becomes very difficult to detect plagiarism,” said Ashley Lowry, McLean’s technology specialist. “We know the students who are doing it. If you ask any teacher, they would be able to spot AI, but it’s harder to find proof.”

Reshaping education

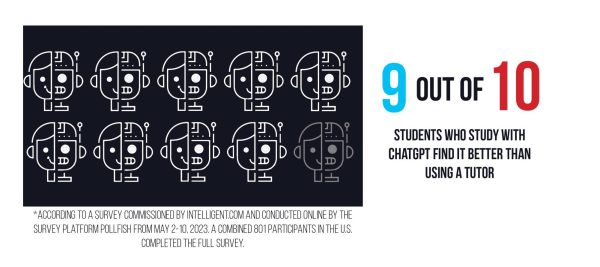

Despite the challenges that come with any revolutionary technology, it cannot be overlooked that AI is set to help personalize learning for students in the coming years. Since generative AI can produce human-like text and explanations, many students have started to use chatbots as personal tutors. In The Highlander’s survey of 223 McLean students, 63% reported that AI makes learning easier.

A number of products have been riding the AI education technology wave, including Delilah, an AI tool that Harvard students developed in 2023 to assist students with their writing process. Developers trained Delilah on the writing structure and styles for college application essays and popular Advanced Placement (AP) classes.

“I wanted to build a tool that would help everyone tell their true stories in the most compelling form so that whenever they write, their essays wouldn’t face a loss in quality of writing,” said Delilah founder Khoi Nguyen, a Harvard student from Northern Virginia. “I knew that a lot of people had great stories to tell, but they didn’t have the ability to write these stories or the ability to write good essays.”

Nguyen is one of several entrepreneurs in the U.S. who has recognized the value in accessible AI tutoring. The emergence of AI tutors like Delilah that are capable of providing high-quality learning is a major benefit of integrating AI into education.

AI can also personalize education through data analysis. With existing models, AI can identify patterns and trends in student data, giving teachers critical insight into what each individual student needs.

“An AI model could pick up what strengths and weaknesses a student has in a more continuous and subtle manner than current testing protocols allow for,” Das said. “AI can look at a student’s history over time and compare that with the data of very large numbers of students from the past and then predict what kinds of teaching strategies or materials would best serve that student.”

AI’s analytical potential can also bridge inequities within schools.

“AI can identify subtle patterns that are difficult for teachers to [find],” said AI ethics expert Benjamin Xie, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University. “[Educators] can use statistical tools to identify when an exam might exhibit some accidental bias towards a certain group and therefore disadvantage another group. AI tools can be really great at identifying nuanced patterns that could reflect potential inequities which teachers could then address.”

Although at the moment there are concerns about AI worsening socioeconomic gaps in education (see section titled “Pitfalls and paths forward”), generative AI tools accessed through the internet do have the potential to level inequities stemming from wealth disparities if adopted properly.

“The reality of personal tutors is human capital. You can’t have a high-quality teacher everywhere and give that opportunity to every single student in the country,” Nguyen said. “[AI] transcends that barrier — you aren’t limited to where you’re born or whether or not you had the money to purchase textbooks and professional teachers.”

One of AI’s most impactful changes will be its power to bridge gaps, improving inclusivity in the classroom. Language barriers prevent students from receiving a full and effective education, and under-accommodated learning disabilities can have devastating effects on students. AI can help level the playing field.

“Imagine a child who has some challenges identifying other people’s emotions. The child wears AI-enabled Google Glass, and the glasses can detect emotions and reflect that on the glass,” said Daniel Schwartz, dean of the Stanford Graduate School of Education. “This can give children the confidence to interact with other people because they can tell how other people are responding to them. There are going to be many applications of AI that will help children with special needs.”

AI could also reduce teacher workload through the automation of time-consuming work, including grading papers and lesson planning. Similar to digital platforms that grade multiple choice assessments immediately, AI could automate the grading of open-ended or free-response questions.

“If we can reduce the time spent on grading, we can allocate that time towards working with students on a more individualized basis or hosting and building instructional materials that are more personalized,” Lowry said. “Students will benefit from all these things, so I just try to think about the prioritization of tasks and how we can delegate tasks to AI to free up teachers to do the more critical work.”

While automation could be used to save teachers’ time, its implications extend far beyond streamlining tedious jobs. Automation has the possibility to intrinsically change learning. Since AI will be able to complete many tasks for humans, the question arises of whether or not this makes learning certain subjects unnecessary.

“It comes down to a question of what we’re trying to teach. It’s going to continue to be important for students to know how to read critically, communicate clearly, write persuasively and reason quantitatively,” Das said. “[As long] as tools like ChatGPT interfere with those goals, we need to be careful in allowing the use of such tools in the classroom.”

While it may be important for students to retain skills such as communication and critical thinking, it is possible that AI will be able to partially automate other traits such as creativity. For instance, users can prompt a chatbot with a problem and receive hundreds of ideas, which may help students in open-ended subjects where there are multiple ways to solve a problem.

“[AI] is a good place for idea generation — to kind of see what the most obvious image to come up with for an art prompt is,” AP Digital Art teacher Allison Dreon said.

This function of AI can be effective for brainstorming across a variety of subjects.

“I find that AI is particularly useful when I’m doing history because there are a lot of events that I need to know, and some of them I might not have remembered, so using AI to come up with those events is really useful,” McLean junior Marcus Choi said. “Using AI to help me brainstorm gives me a line of thinking that I can align my brain to, which helps me come up with more ideas on my own.”

AI’s ability to produce ideas can also help teachers with lesson planning.

“If I’m not sure how to design my lesson plan about the history of Chinese immigration to the U.S. during the 19th century, then I might, as a teacher, prompt ChatGPT to generate some potential ideas or images,” Xie said.

Similarly, basic generative AI can provide support to school leaders, with several administrators across FCPS already using tools like ChatGPT on a consistent basis.

“Some principals are using [generative AI] to create letters that go out the community, to write individual letters to families and even help write newsletters,” said Rob Kerr, one of the coordinators of the FCPS Student Equity Ambassador Leaders (SEALS) program.

This school year, FCPS has approved ChatGPT and Google Bard for staff use, even training staff on how to use the tools in some regions.

Student opinion at McLean is split over whether AI should be integrated for classroom use, with 48% of McLean students believing that FCPS should integrate AI into classrooms according to The Highlander’s poll of 223 students.

Many of the current limits on education have existed for decades; leveraging the expanding capabilities of AI in the right ways will bring public education closer to fulfilling its potential and prepare students for the future.

“I’m conflicted [over AI integration] because a lot of future jobs are going to use it, so cutting [AI] out completely wouldn’t be beneficial,” Enos said. “We’re in a new era.”

Pitfalls and paths forward

Apart from plagiarism, the integration of AI in education does not come without its fair share of downsides. As a new technology in the education sector, generative AI will continue to change learning in an unpredictable fashion, which comes with the risk of widening the opportunity gap.

“Looking at the history of educational technology, not even involving AI, from the phonograph or even further back [to] books, to more recent [inventions] like the internet, we see that educational technologies tend to exacerbate or worsen educational inequality, which often widens socioeconomic gaps,” Xie said.

Across FCPS, different areas have varying approaches to staff training on AI tools, despite the county’s uniform AI policy, revealing significant disparities between regions.

“We [would be] growing inequity across the school division if we only [use AI] in certain pockets across the county,” Kerr said.

Even though less advantaged schools would benefit the most from adopting innovative technology with long-term benefits, the schools that have the money to embrace AI are actually the most likely to do so. Ironically, the same technology that has the potential to level playing fields in education are, at the moment, worsening the existing opportunity gap within FCPS.

“A school that has access to better resources, like internet connectivity, laptops, funding for student lunches or training for teachers might use AI tools in a clever way in their classrooms, like complementing a student’s art or using AI-generated images to learn more about different historical moments,” Xie said. “An [underfunded] school with teachers with less training on AI might use it in more simple [ways] that either don’t maximize the potential benefit of AI tools or potentially use them in ways that accidentally perpetuate stereotypes and norms.”

Another concern is in regard to the development of students’ AI literacy, which is the set of skills necessary for students to navigate the new technology. Similar to the internet, students and teachers need training to effectively and responsibly navigate AI.

Addressing this issue, McLean students partnered with the Girls Computing League to organize a student AI summit at the Capital One Center in Tysons Corner last August. McLean Principal Ellen Reilly and FCPS Superintendent Michelle Reid both spoke at the event. The summit was geared towards assessing how AI will impact education and preparing students for the future of AI in the workforce.

“The summit was aimed to educate high school students on how artificial intelligence is transforming many industries across the world,” said sophomore Rishi Bathala, one of the event organizers.

Some believe the most effective way to understand AI’s transformation of education is with a head-on approach.

“GPT has so much potential already. The only way to ensure proper use of AI is if we embrace it as quickly as possible. By adopting a faster approach, we first reveal how we can best utilize GPT,” Nguyen said. “We haven’t figured that out, and the only way we can figure it out is to adopt it more and to address the concerns.”

Change is difficult; teachers and school divisions understand that. Nonetheless, even if AI is not officially adopted in a classroom setting, it will inevitably continue to transform education in the coming years.

“We, as an education system, need to be more like Netflix and less like Blockbuster,” Kerr said. “We need to be on the cutting edge.”