The internet allows for an open exchange of information, making worldwide news accessible to everyone. Unfortunately, this same openness allows for the spread of misinformation and disinformation, which is intentionally deceptive. This issue has always existed, but misinformation is becoming increasingly difficult to identify because of AI enhancement.

With the upcoming 2024 presidential election, misinformation is bound to reach new levels of influence. As such, media literacy — the ability to determine the accuracy and credibility of media — is more important than ever. Adults need to critically examine news sources and err on the side of skepticism when looking at suspicious images or statistics.

In order to prepare McLean students to navigate the ever-evolving sea of misinformation, English 9 and 10 classes should have media literacy units that focus on up-to-date verification strategies for online information. According to Media Literacy Now, an organization dedicated to teaching media literacy skills, only 38% of adults have had a formal education in analyzing media messaging. Future voters are in high school right now, and they need to be prepared to decipher fact from fiction.

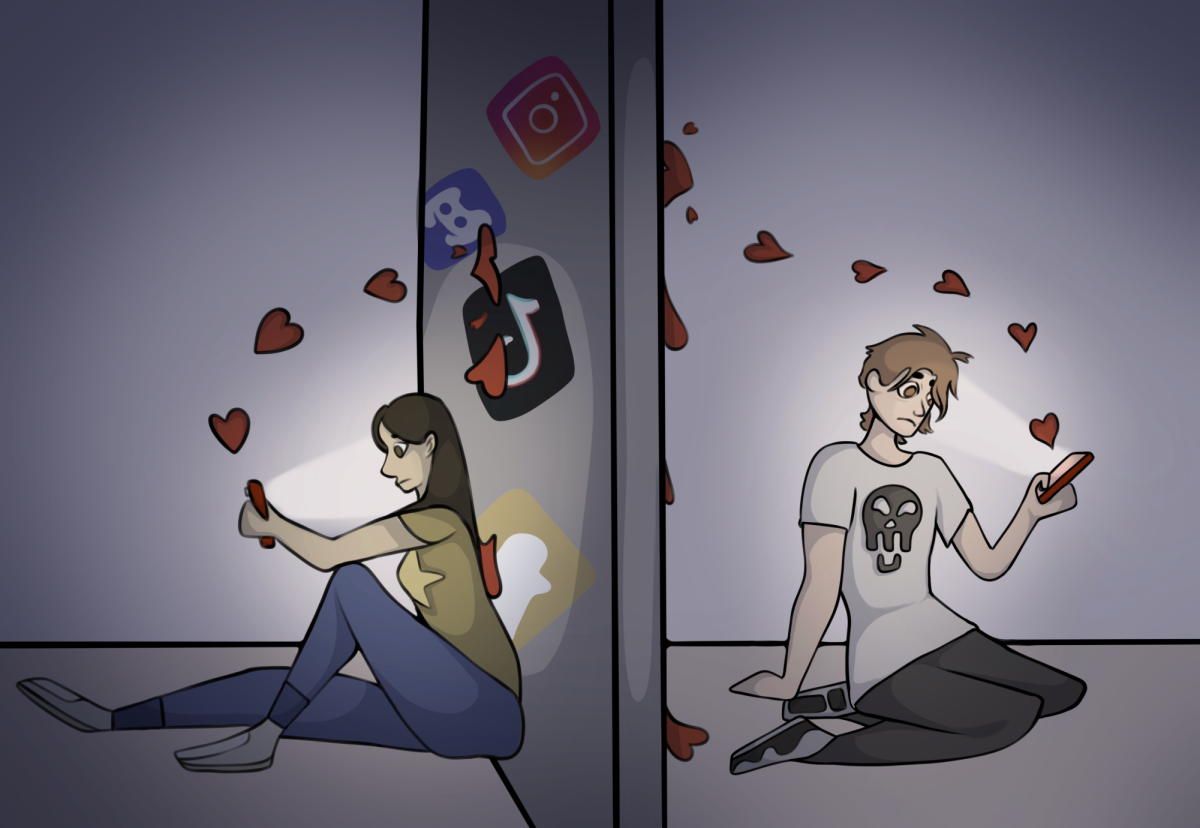

English classes at McLean have research units in which librarians show students how to critically verify sources, but these sources are primarily FCPS-authorized databases and universally accepted news sites like the Associated Press or the BBC. In reality, the majority of young people get their news through social media. Even those who turn to established publications will inevitably consume most of their information on social media platforms, especially high schoolers who are active on short-form video apps like TikTok and Instagram Reels.

Schools should teach comprehensive media literacy with updated strategies to spot misinformation in a digital era. Students should learn methods of identifying AI-generated texts: noticing the overuse of vague words and phrases, training to pick up on a lack of personal touch in writing and spotting perfect spelling and grammar. AI will continue to develop, so it is necessary that any media literacy curriculum adopted is reevaluated yearly.

Part of the misinformation problem is that people ignore blatant disinformation and don’t realize when more subtle falsehoods have fooled them. Disinformation usually is not absurd and obvious; most is manipulated information that can alter news beyond a simple bias. Exposure to misinformation and practice identifying it in a classroom setting is one way in which schools can teach students to be more media literate.

Another aspect of misinformation that schools should address in classrooms is the effect of groupthink. The mass circulation and approval of misinformation can make identification more difficult: because the information seems to be widely accepted, it goes unchallenged. Schools should teach students how groupthink can harm their perception and to remain vigilant even when looking at reposted and reaffirmed content.

In order for schools to train students to identify misinformation in multimedia, they should incorporate hands-on social media training in class. After all, the most important content for students to learn to navigate is on the platforms that they use the most. By comparing accurate, truthful posts with intentionally misleading content, students would learn to effectively weed out false information on social media sites.

Currently, the only class in which students can truly learn media literacy skills is journalism. By covering current events and creating a publication, students gain the perspective of a reporter and editor. Still, journalism is an elective, and media literacy is a universal skill that should not be hampered by a student’s course selection.

As such, English classes at McLean should have a unit in which students learn about misinformation and how to identify it. In doing so, students will become well-informed, media literate citizens, capable of making responsible political and civil decisions.