The recent efforts to ban books in Virginia schools show a bleak future. Last school year, two books with LGBTQIA+ characters, Lawn Boy and Gender Queer, were temporarily removed from FCPS’ library, before being returned after student protest. This and last year, the backlash has extended to the General Assembly. Book ban bills in the state legislature should raise a red flag to everyone, as it uses political power and recognition to fuel a dangerous phenomena.

Last year, a bill passed that required schools to notify parents when instructional content included sexually explicit materials. However, when Virginia’s definition of sexually explicit includes homosexuality, the law effectively shames LGBTQ+ people for their existence.

This year, other dangerous bills are being considered.

HB 1448, which passed the Republican-controlled House of Delegates on Jan. 26 on partisan lines, would require the Department of Education to consult stakeholders to outline model book removal procedures for school districts in Virginia. While the bill explicitly includes local school boards, public school librarians, and parents as stakeholders, it does not require students to be included as stakeholders. Given that students are the actual demographic that reads the books in school libraries, the bill has the potential to silence important input from students.

Del. Simon (D-Fairfax County) attempted to insert an amendment to HB1448 that would prohibit school districts from removing books solely on the basis of the presence of a protected class. Protected class refers to a group of individuals protected by anti-discrimination law. The amendment would have ensured that books weren’t banned simply because of the presence of a racial minority or LGBTQIA+ person. Still, Simon’s amendment died on partisan lines. Bills like HB 1448 sound mild when verbally explained, but contain real implications for students and members of a protected class. While the fundamental idea of protecting young people from “harmful” literature sounds great, grouping the presence of marginalized characters with sexually explicit books for a political statement devalues the legislative process.

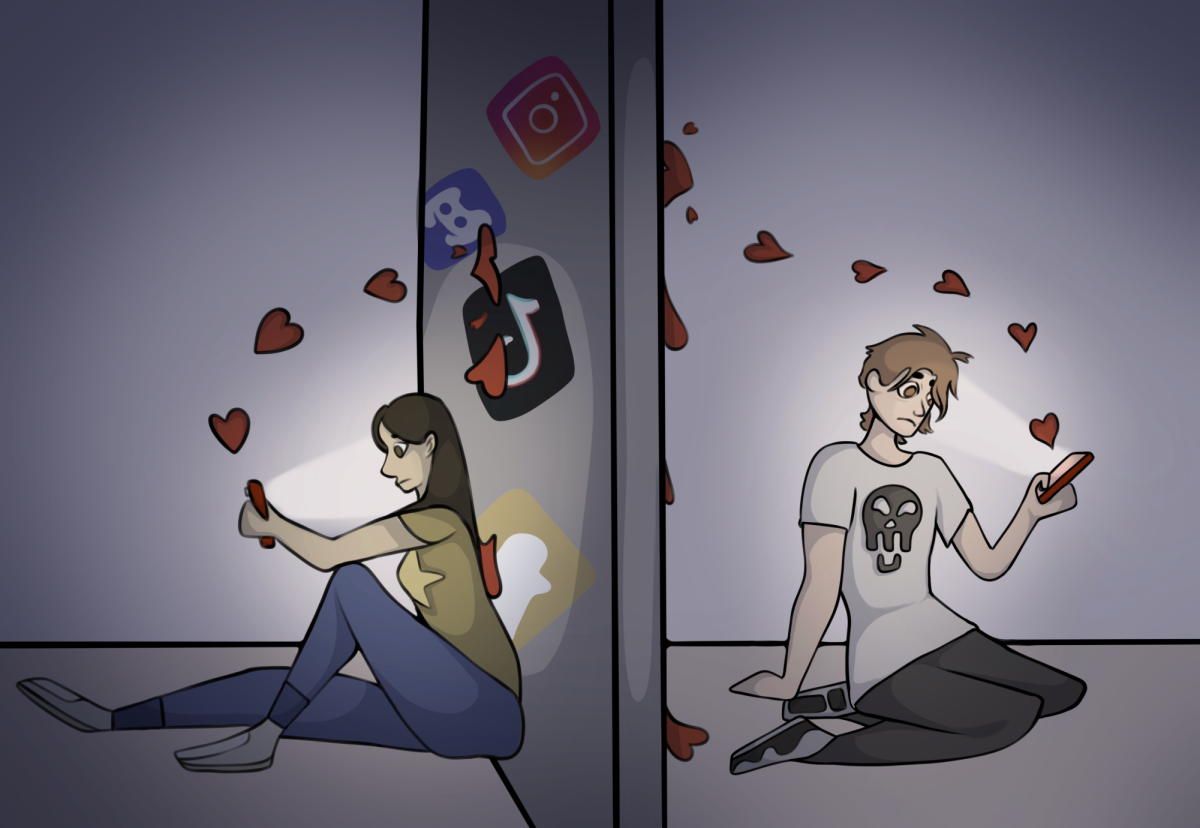

Not only do book bans attempt to shelter students from reading about diverse experiences, it is unrealistic to expect that a book ban will stop youth with internet access from knowing about the real world. HB 1448 rests on an unfounded standard that students will be protected through the sterilization of educational materials.

Another bill, HB 1379, proposed by Del. Anderson (R-Va. Beach) would require school districts to compile a spreadsheet of content identified with “graphic sexual content.” The bill would also allow parents to prohibit their students from reading any material identified with graphic sexual content, regardless of the age of the student or their grade level. The bill passed the House of Delegates on partisan lines. Especially for students who are nearing 18, being blocked from reading about the real world is bound to have negative consequences in a student’s life. Schools should be preparing students for their adult life–when a student is the last person in their future work or school community learning about the existence of people with different backgrounds, that’s not going to help anyone.

While both HB 1379 and HB 1448 meet an uncertain fate in the Democrat-controlled State Senate, the bills are a dire sign of where education policy is headed towards today. Book bans should be stopped from progressing further as they stunt a student’s learning of the real world.