Mock(ing) Congress

AP Gov classes write bills and debate legislation

Representatives participate in their General Assembly. As in real life, parties sat on opposite sides of the room and didn’t hesitate to vote along party lines.

January 8, 2020

Tampon tax removal, mass incarceration, nuclear energy recycling. Farmer tax breaks, and transportation reformation. The banning of gay conversion camps.

These are the issues AP Gov seniors want Congress to address.

“I honestly didn’t know what a bill was before this [project],” senior Jerrick Bravo said. His bill sought to decrease carbon emissions by disincentivizing individual transportation. “It was a great experience in learning what a bill is, how it’s passed, what the roles of congressmen are, and how our government works.”

First, students were randomly assigned to either the Democratic or Republican party. They then elected party leaders–the Speaker of the House, who heads Congress and leads the majority party; the Majority Leader, who represents the majority party; the Majority Whip, who assists the Majority Leader; and the Minority Leader and Whip, who are the minority parties’ counterpart to the aforementioned roles.

Students also chose Chairs for four Committees– the Education & Labor Committee, which legislates for students and workers; the Ways & Means Committee, which influences the federal budget; the Energy and Commerce Committee, which regulates energy, health, the environment, and commerce; and the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, which presides over all forms of transportation.

The goal of Mock Congress was to exhibit the fundamentals of the institution while working with the time and size constraints of a class, not replicate the many processes exactly, so some party roles and committees weren’t represented.

After electing leaders, students chose a state and district to represent that related to the issue of their bill.

Then came the most intensive part: writing the bill at home.

“A lot of work goes into this, and you don’t want to be researching something you think is very boring,” senior Bela Bhatnagar advised upcoming seniors. She also said to pick relevant topics, as it’s harder to get people to fund an issue they don’t care about.

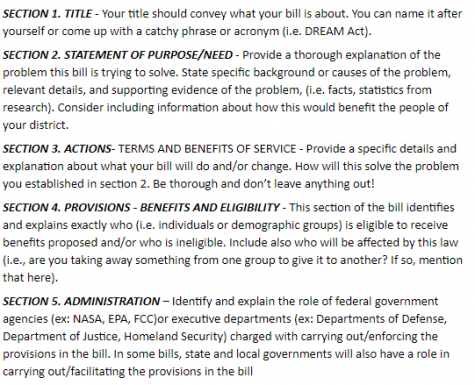

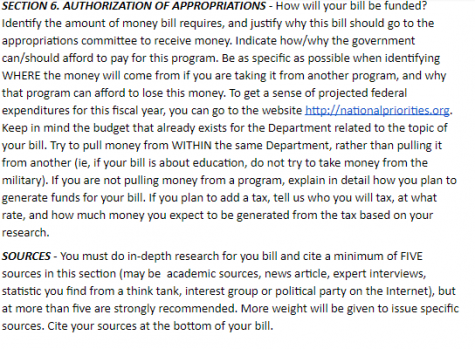

Students identified the situation they sought to change and then explained how their bill would change the situation, who would be eligible for the changes, how the federal government would implement the changes, and what funds would pay for the implementation of all of the above. Here’s the rubric:

The “representatives” gathered in their Committee groups and met to “yea” or “nay” proposed legislation. In Congress, representatives cannot speak out of turn–their Committee chair must give them permission to be heard. But in Mock Congress, the rules of decorum were sometimes overlooked.

The “representatives” gathered in their Committee groups and met to “yea” or “nay” proposed legislation. In Congress, representatives cannot speak out of turn–their Committee chair must give them permission to be heard. But in Mock Congress, the rules of decorum were sometimes overlooked.

“When your in small groups like that, and you know each other, its difficult to follow that,” said Bhatnagar, Chair of the Ways and Means Committee. “I really did not recognize everyone to speak, like it was a lot of back and forth.”

Conversations were more or less productive.

“I think it was pretty fair,” Bravo said. He was in the Transportation and Industry committee. “We all got to explain the reason behind [our bills] and where all the funding came from.”

““My committee was so dry,” Bhatnagar said. “We had three bills focusing on lowering the cost of college for students and so it got very repetitive and boring. And a lot of us dealt with finance, which can be difficult to understand, so it wasn’t really like, as interesting as it could have been.”

Those that made it to the general assembly presented their bills to the entire class, in attire slightly more formal than that of the average day. They explained the purpose and details of their bill and attempted to refute any opposition. Their goal: a majority vote that sends their bill to the Senate (or in this case, another Gov class).

“My speaker of the house was very commanding, but not in a bossy way,” Bhatnagar said. “She knew all the rules and decorum, she knew what to say, she managed well.”

Bravo said that funding was the biggest reason bills didn’t get passed. “People just didn’t have an appropriate source for their funding, or they just didn’t allocate where their funds would go.”

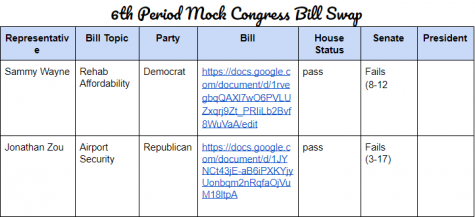

In the end, only a select handful of bills made it past Committee, General Assembly, and the Senate. Closing the gun show loophole, banning gay conversion camps, and preventing the justification of transphobic murder were among the bills passed.

Interestingly, there was a difference between the votes in one classes’ General Assembly and the votes in another classes’ Senate on the same bill–some bills that passed near unanimously in one class were heavily denied in other classes, and some bills that barely passed in one class passed unanimously in the other. This could have been impacted by the fact that In the General Assembly, a representative explained their bill and answered intense questions, but in the Senate, the representative wasn’t present and the class read the bill with no supplementary commentary from the writer.

This project raised many questions, the primary of which were: does our Congress effectively represent its people’s concerns? Did this project accurately mimic the workings of Congress? The biggest complaint about both the workings of Congress and AP Government’s mimicry of it seemed to stem from one thing: partisanship.

“I feel like [the project] wasn’t a true representation of [Congress],” Bhatnagar said, “because if you really wanted to simulate congress it would be very partisan, and very divided. Our bills didn’t have to follow party ideology. [If they had] Paul’s bill on gun control would never have been enacted by the Republicans, cause it doesn’t follow their ideology necessarily.” She also said that the class got “pretty partisan” on that bill.

“Even if I was a Republican, I still took a more liberal stance on things when we voted,” senior Bharathi Ganesan said. “But we [the class] voted across party lines. I was representing a republican district, and trying to represent how, like, actual Congress goes, and they vote along party lines.”

Earlier in the year, classes anonymously completed and reported their political alignment. Results show that every Gov class–except one that was evenly divided–was predominantly liberal. AP Gov teacher Karen MacNamara said that teachers couldn’t accurately reflect party lines because there simply aren’t enough Republicans, but that even if there were, they would still be inclined to randomly assign party affiliation instead of basing the project off of identity.

Some students, like Bravo, thought the project was compressed into too short a time, and that it would have been more fun if students had time to “find more extensive answers and create an even stronger bill.”

Others disagreed. “I thought it was fun. But knowing how congress works is pretty simple, and like, I could have learned this from a video, or the textbook reading,” Bravo said. “All this really taught me is that, like, it takes a lot to write a bill. It’s not the only way to learn about the workings of Congress. And it wasn’t the fastest way, or the most efficient way, but it was probably the most interesting way.”